In (Moderate) Defense of 1934’s Stingaree

Stingaree (1934) is an odd bird, especially in 2024; it bears the special distinction of having lost RKO $49,000, despite the massive success of its stars in 1931’s Cimarron. It is undoubtedly hindered in part by its historical Australian backdrop, in addition to a fantastical plot that is so far removed from the realm of possibility that you have to come from the fairytale angle to enjoy it—quite the feat for accomplished realist William Wellman.

Not only has Stingaree bore a cross outlined in red tape for decades, its eccentricity and lush operatic sequences means its appeal is simply lost on most modern audiences; even viewers in 1934 were a tad unsure what to think. Legal ownership squabbles and the ever-changing tastes of the average moviegoer are, yet again, woven into the history of a maligned film; Stingaree may deserve a portion of its middling reputation, but the dash of pre-Code salt saves it from being too saccharine, giving it some reason to avoid being unfairly resigned to oblivion.

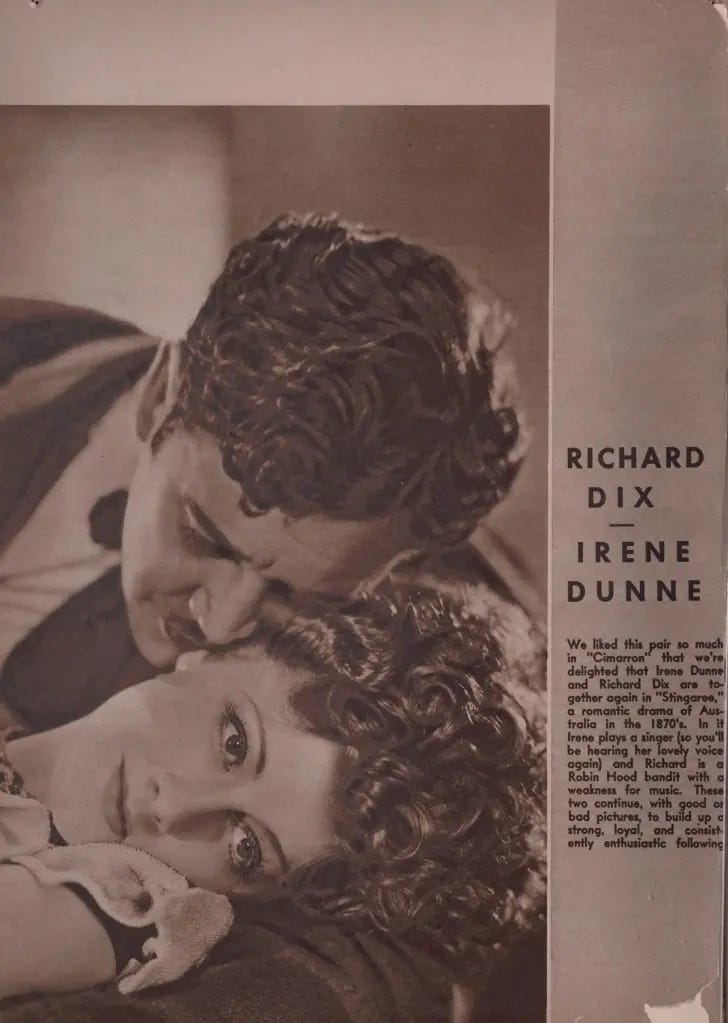

Beyond the back-and-forth dialogue with Joseph Breen that undoubtedly warped Stingaree to begin with, it’s worth mentioning that the passage of time has not been kind to the memory of dashing leading man Richard Dix. Most are chiefly familiar with him in the aforementioned Cimarron, and beyond that, his celluloid persona is obscure. Dix’s early demise from alcoholism certainly hasn’t helped his cause, and as a result, the burden of navigating Stingaree’s daunting exposition falls squarely on Irene Dunne’s shoulders, as Dix vanishes for most of the film.

Even Irene’s mesmerizing versatility can’t seem to keep more than an enclave of wizened film buffs in line to go to bat for Stingaree, especially when she starred in classics like The Awful Truth that are leagues above it. While she certainly gets her due in classic film circles today, you’d be hard-pressed to pluck more than a handful of seasoned Irene fans from the general public; and so Stingaree remains an isolated prize for those who recognize its shiny facets, not unlike the musical jewelry box given to Irene’s Hilda by the swashbuckling title character.

At its core, Stingaree is the Robin Hood of romance, with the titular bandit (Richard Dix) chiefly focused on his liberation of wretched servant girl Hilda (Irene Dunne) from Mrs. Clarkson (Mary Boland)’s aristocratic clutches. As many have pointed out, he steals from the rich not in the interest of the poor, but because that was apparently just his sense of humor.

The mustachioed outlaw becomes enamored with Hilda when he is greeted at her domicile by the lovely sound of her singing at the piano—this, of course, comes directly after his abduction of a noted composer Hilda was conveniently expecting as a visitor. He is so taken with Hilda that he offers to help her win an illustrious career while posing as Sir Julian, the kidnapped composer.

Outlandish premise aside, the film’s best scene arrives after Stingaree’s true identity is revealed; he flees with Hilda into the dense, dark forest. There, among the backlit spindly branches, he tells her she has a great voice, a great future, and that he wants her to ‘have it all’.

“Do you always get what you want?” asks a disheveled Hilda of her kidnapper as he stares her down. “Always,” he replies, “sometimes I’ve had to wait a long time for a coach that I’ve had designs on, but sooner or later she comes along…and I rifle her for everything she has to give.”

He presents Hilda with a stolen trunk of the latest London fashions and asks if she wants to be a servant girl or a singer as she hesitates to slip out of her dress, her back to the camera. “Singer,” she replies with a sudden fervor before the two kiss and fade to black.

Stingaree and his sidekick whisk Hilda, clad in her ‘borrowed’ gown, to a recital where her former employer is performing for an escaped Sir Julian. He holds the partygoers at gunpoint and forces them to listen to Hilda instead, where the revered Sir Julian realizes the servant girl’s talent.

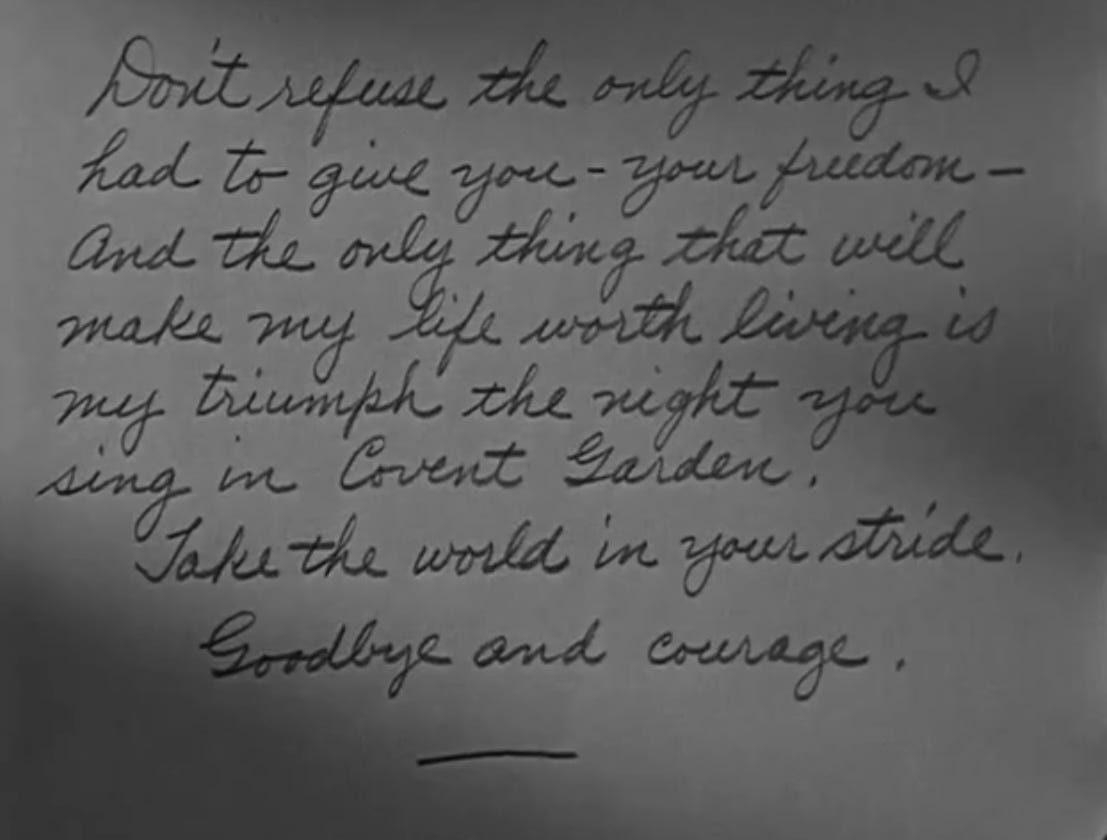

Hilda leaves with Sir Julian for a musical tour of Europe after her beau is captured; briefly she balks and tells her new promoter that her place is with Stingaree in Australia. A gift from him in the form of a music box is brought to her, perfectly on cue, and this note is inside—

No more prodding is needed and Hilda goes on to take a whirlwind tour of the most prestigious opera houses on the old continent, which culminates in her long-awaited London debut. Sir Julian has fallen for her and she reluctantly marries him, though she is plagued by persistent reminiscences of her night with Stingaree.

Hilda finally gives in to her desire to be with Stingaree on the eve of her honeymoon, telling Sir Julian the convict had given her “all of this” while gesturing broadly to the grandiosity around her—she is giving up her career to find her true love. The camera pans to a figurine of a knight in horseback on the mantel, and after a series of far-fetched escapades that take place during her final concert in Melbourne, Hilda reunites with her raffish hero and rides off with him into the chiaroscuro forest.

Stingaree’s ending is not entirely storybook. The conclusion of Hilda’s final concert is punctuated by a Wellmanly volley of staccato gunfire that follows her beau out the theater doors as she collapses onstage, reminding us this is still a film by the man behind The Public Enemy.

Stingaree saw its wide release in May 1934, mere months before the integration of the more stringent Code and during a turbulent time in Hollywood which wreaked havoc on production. City exhibitors in Motion Picture Herald were generally ‘so-so’ or unhappy with the turnout, though a minority in Eminence, Kentucky held out that Stingaree was “one of the very best pictures we’ve played lately.”

Other than that, period reviews speak to the box office losses. John Scott of the Los Angeles Times called Stingaree “impossible but interesting”, and Variety hit the nail on the head with its take that it was “more Hollywood than Stingaree” and “smoothly, if illogically, plotted”.

“Maybe the younger femmes will go for it strong, but the improbabilities in the plot certainly tax the credulity of the more sober minded audience,” wrote a reviewer in The Film Daily, which harks back to the incongruity of Stingaree’s setting, at least in 1934; it is essentially somewhat of a rags-to-riches Depression story fixed in 1874 Australia, which renders some of its relatability moot.

Though it’s far from a tale of female empowerment, Stingaree’s Hilda isn’t a one-dimensional hapless heroine, either. The titular hero didn’t force her into a musical career; he encouraged her after she related her dream of singing for Sir Julian. Hilda also told Stingaree of her late mother who forsook her musical career for marriage; his note to Hilda pleads with her to avoid making a similar mistake.

Contemporary reviewers penalizing ‘dragging’ operatic scenes are either musically inexperienced or taking Mary Boland’s comedy at face value; each song is concise and engaging, especially Dunne’s rich rendition of “Tonight is Mine”.

If anything, the oversaturation of “Stingaree Ballad” as background music throughout the first half of the film detracts from its melodic charms. Dunne’s classically trained voice is nothing but a delight, as it is in Roberta, released the next year.

Another band of negative reviewers, both of the era and contemporary, hold tight to Stingaree’s fairytale nature, picking apart its sheer implausibility as a fatal flaw. One thinks of the fact that its Melbourne sequences were filmed on the old Phantom of the Opera set at Universal; while it’s far from unfair to harp on Stingaree’s whimsical nature, this context lends it some degree of authenticity, at least for this writer.

Stingaree of course has its place, not only for the adventurous Dunne fan, but for pre-Code enthusiasts and Wellman completists alike; the peculiar Western-musical mix makes it worth at least one watch, especially for those who enjoy standard historical romance and a good Walter Plunkett gown.