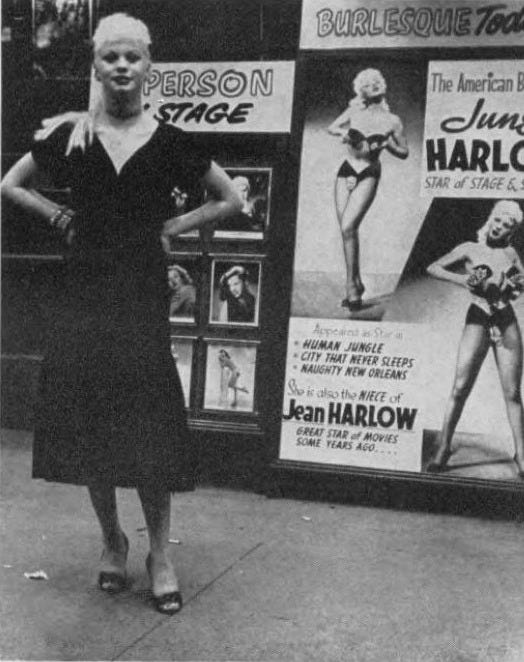

A particularly relevant and refreshingly inarguable fact about Jean Harlow is that she was an only child. This didn’t hold much weight for bottle-blonde hopeful June Harlow, who played the game many did in mid-century show business to either get a foot up into Heaven’s oligarchy or simply irritate the angels in residence; claim to have been there, like Kenneth Anger, or claim a relation. June chose to play the dear teenage ‘niece’ of the original platinum blonde, and did far from a terrible job; over half a century later, mislabeled clippings from someone’s dead uncle’s stash of nudie mags showing June’s bared leg and half-obscured face are still sold, bought, and enjoyed under the impression of them being her ‘aunt’, which certainly counts for something.

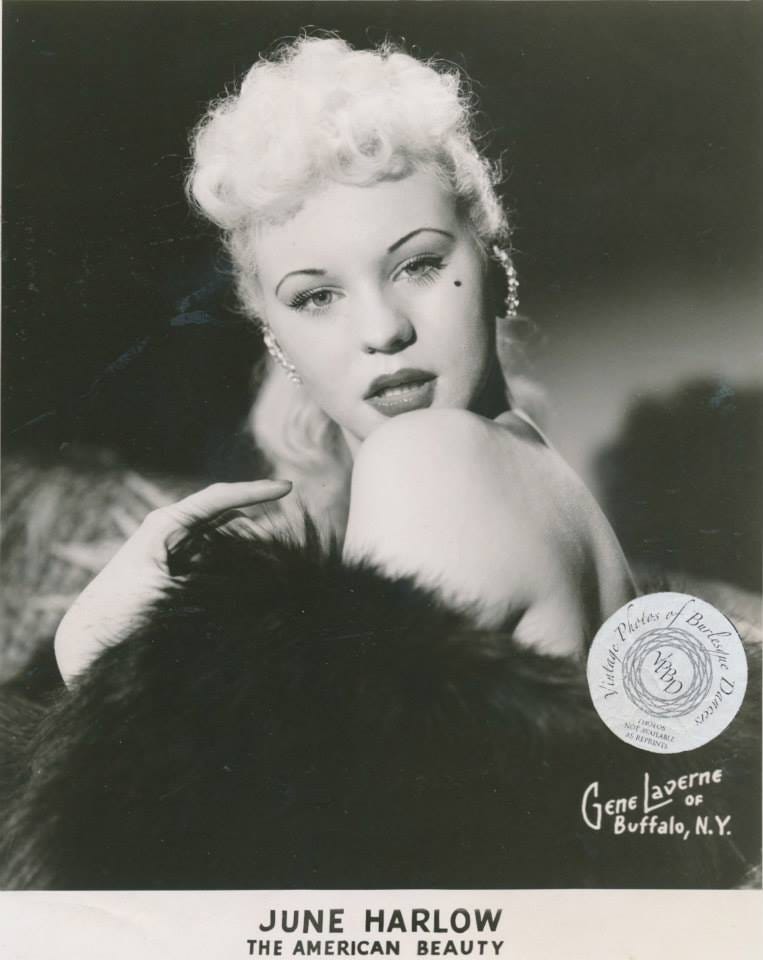

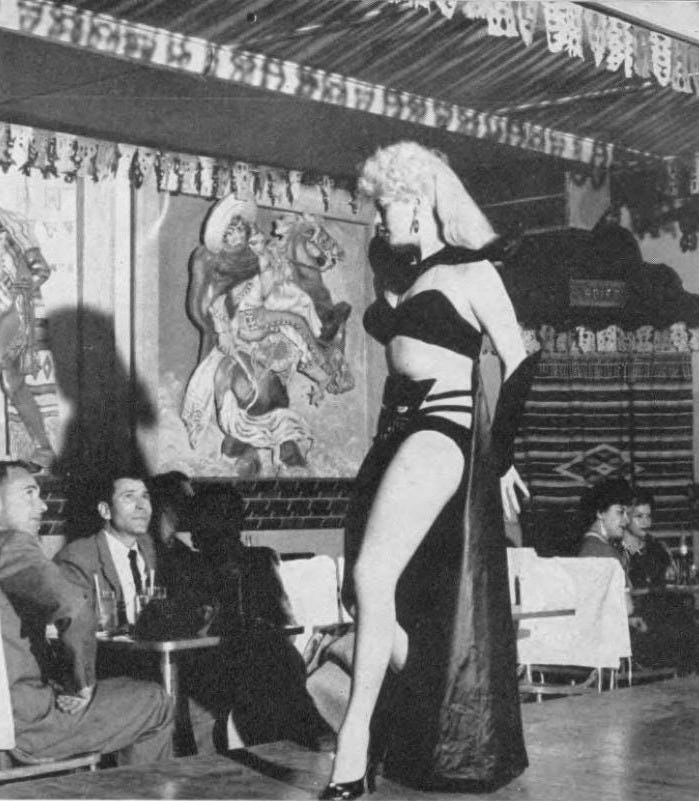

The year is 1955, and movie starlet (an adjective underscored with three exclamation points) June Harlow DiMaggio—a ‘sister-in-law’ of Marilyn Monroe, to boot—debuts on the Fort Worth burlesque circuit as the headliner of a French Can-Can show in the city’s Skyliner Ballroom. A prominent cleft chin, a pouty complexion with a cleverly placed beauty mark, and a fluffy head of white-blonde hair atop a killer hourglass figure are more than effective in putting her case over.

Anthony ‘Tony’ DiMaggio (sometimes ‘Russ’) would materialize by her side some months later as her husband, or maybe just her boyfriend, but her emcee and promoter either way. Successful like many other twentieth-century strippers in keeping her birth certificate out of her business life, the truth of June Harlow’s origins are a near mystery to this writer, and the same can be said of DiMaggio, the non-nephew (or brother) of Joltin’ Joe whose undeniable wide-lipped Roman resemblance to the famous ballplayer allowed him to skirt by as a theoretical relative. What’s certain is June and Tony couldn’t have been more than very distant cousins to their famous counterparts, and their success in swindling their way into lucrative nightclub careers through vague connections to bigshots and blondes renders whoever they really were almost irrelevant. For all intents and purposes, they were Harlow and DiMaggio, and their dual performance is entirely respectable in its dedication--the Anna Andersons of fifties counterculture.

IMDB reports June Harlow was born in August 1920 and died the same month in 1985, key dates that upon investigation were found to belong to a wholly unconnected Floridian housewife of a similar legal name. This would have made June around thirty-five when she appeared in the September 1956 issue of Cabaret magazine with arms akimbo next to “I STRIPPED AT 16” in bold, which wouldn’t be entirely implausible, except reading the article readily reveals teenage June’s claim that ‘Aunt’ Jean Harlow died ‘just a year’ before she was born.

In addition to the activity in the title, which she credited with giving her a ‘head start’ on other girls now that she was eighteen, June also talks of leaving Kansas City at thirteen, getting hitched to DiMaggio at seventeen, and using burlesque as a doorway from which to ascend into the ultimate stardom—movie stardom, which she hoped to attain by twenty-three. Evidently, June had done her due research on her iconic ‘aunt’, as here and in other interviews she correctly recalls Jean Harlow’s time and cause of death, hometown, and birth name, opting to borrow the publicity-spiced version for her own: ‘June Carpentier’.

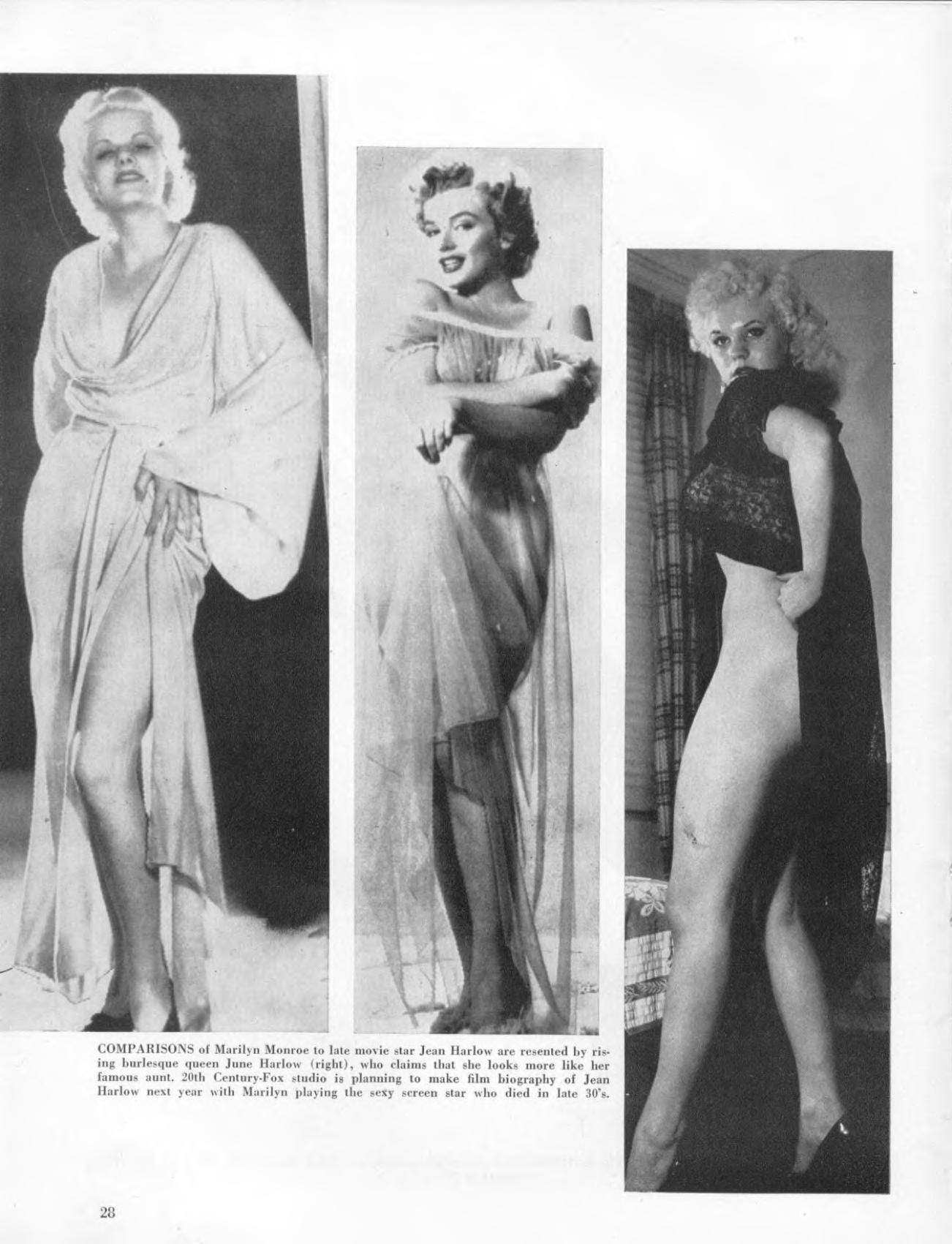

“I hope I’ll be able to fill my Aunt Jean’s shoes before long,” June mused in Cabaret about the much talked-of Harlow biopic which wouldn’t materialize for another nine years, “Don’t get me wrong. I don’t want to ride on her fame. I want to be an individual and reach stardom on my own merits. But there is another actress whose name I'd rather not mention who has been called “the second Jean Harlow." and has made a lot out of it. This burns me up. I think if anyone is going to be the second Jean Harlow, it should be me. After all, blood is thicker than water, and while I don’t think anyone could top Aunt Jean, I feel that I can come closest.”

June mentioned that other actress the same month to columnist Will Jones—her own ‘sister-in-law’. “They’re going to make a movie of her life,” she said of Harlow, “and Marilyn Monroe is supposed to be in it, but it’s not definite about Marilyn Monroe. I’ve talked to an agent, and he told me to get some dramatic lessons. I hope I can settle down in a town like New York for a couple of weeks, and get some.”

The scheme was genius if not extravagant: capitalize on one fake relation, try two more on your man for size and added leverage. She went as far as to take an extra potshot at Monroe for ‘losing her friends’ in light of her divorce from Joe DiMaggio: “I read in the paper that she and her new husband [Arthur Miller] went to an intellectual play in London. It was a flop.”

Perhaps fueling some of this bitterness towards Monroe’s popularity, more than the publicity bait, was the fact June had already flopped out of a handful of films just as the gates to ultra-stardom were opening for the older blonde. The Cabaret article notes June’s bits in Beneath the 12-Mile Reef and City That Never Sleeps (both 1953); following those were Naughty New Orleans (1954), a low-rent nudie little more than a filmed floor show, and the Jan Sterling-powered Human Jungle (1954), a Poverty Row noir with crowded nightclub scenes just big enough for a bushy head of platinum blonde hair to hide in. No further credits materialized, and an obscure film-and-television studio sued June, who had instead skyrocketed to nightclub notoriety, for breaching her contract years later.

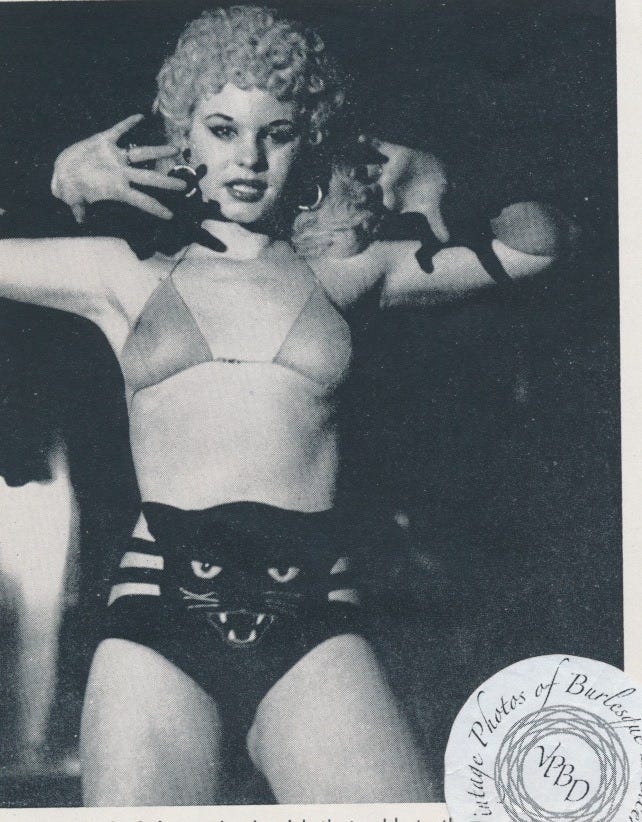

June loosened her grip on the Harlow biopic and left Hollywood film in her rear-view altogether to sell her wares freelance on the national club circuit, managing to retain the Harlow facade even while touring through Kansas City. Included among her interpretative dances were her ‘cat dance’, pawing sexily at the floor while crawling on all fours, and the ‘American Beauty’ rose dance, where she tossed the delicate flowers she used to cover herself into the crowd. “I try to portray something in my numbers,” June said of developing her act, “I don’t just come out and take all my clothes off just for the sake of being undressed.”

One Cincinnati columnist who went to see her act did raise an eyebrow at her propensity for unreliable embellishments, writing that over the course of a week she went from quoting her measurements at 39-22-35 to 38-22-35: “The old grind is beginning to take its toll, I suppose.”

June found herself in hot water—not for fraud, but for disorderly nude conduct—twice. In March 1956, she and five other exotic dancers at Minneapolis’ Alvin Theatre were charged with ‘comporting in a lewd manner on stage’ and partaking in ‘suggestive movements and bumps and grinds’. The arrest record listed her age as twenty-one instead of eighteen. Two years later, in February 1958, the ‘wife of a nephew of Joe DiMaggio’ was fined on the East Coast following an exceptionally raunchy performance. She was back on stage in Florida the next month, and spent the winter comfortably warm in El Paso, where she could avoid old-fashioned American persecution by simply crossing the border to the main drag in Juarez and baring all for the patrons of the Follies and Guadalajara de Noche nightclubs to see.

The third time’s the charm, and June’s next brush with the law in El Paso at least saw some variety. She and DiMaggio were accessory arrests in a bookmaking bust served on a house they were staying in as guests in June 1959; unluckily, arriving officers pinned a found bottle of codeine on the couple, and they were whisked away to the county jail on possession of narcotics. June, true to her hustle, was booked into and released from a juvenile detention facility after giving her age as seventeen.

The platinum blonde showgirl with the self-styled title of ‘American Beauty’ bounced around from bills at the Cleveland Roxy to the more free-wheeling Europe, where press releases commended her for bravely undertaking ‘the most daring striptease in the entertainment history of Italy’. Though no known photos of her late 1959 act survive, it was apparently titillating enough for Milanese reporters to blush redder than tomato sauce. “Italian law prevents strippers from shedding as much as they do in Paris, but Miss Harlow, it was reported, went almost all the way,” reads the newspaper account filed under “June Busts Out All Over In Italy.”

June was still avoiding wagging American fingers by the time newspaperman Hoyt McAfee encountered her stripping for a ‘screaming crowd of Texas oil men, racing car drivers, soldiers, and a group of American beauty parlor operators with male escorts’ across the border in Juarez, 1960, where a language barrier in addition to immunity from hometown lewd conduct laws could aid in the longevity of her act and image as the Harlow niece.

As the decade turned over, the radius of June’s engagements suddenly shrank to a pinhole, and their frequency became increasingly sporadic. Instead of gallivanting on newer and grander European tours, June’s home Juarez act was advertised as returning ‘directly’ from the continent for a string of several months; the showgirl wouldn’t venture east of Shreveport for over a year after November 1961, when 1963 finally took her to Biloxi and Pensacola. Tony DiMaggio’s name is no longer announced as her emcee in the El Paso Herald-Post after their 1960 arrest, which so loyally advertised the same doll-eyed, sleepy-haired photo of June for years on end, and he seemingly evaporates from the racket altogether. June kept on, silently headlining the Guadalajara de Noche just two days after Marilyn Monroe’s August 1962 death without as much as selling a snide comment on her former ‘rival’ to the press.

By September 1965, having passed a full year offstage, June had closed up shop in the South and started fresh in the West, with three shows nightly at the Guys & Dolls in Phoenix—a dive from which locals still warmly recalled memories of Sally Rand fan dances, forgotten piles of wartime junk, and boozy neon signs advertising exotic dancers some forty-odd years later. Phoenix marks an oddly appropriate locale for the burlesque career of Jean Harlow’s forgotten niece to run aground, out in the same neo-noirish ribbon of desert where so many dreams still gather dust, whether they’re gambled away or hung out to eternally dry in the amber backyard sun of a clay-roofed retirement home. Despite ostensibly riding the coattails of the dual 1965 Jean Harlow biopics—which June so badly ached to star in back in 1956—her act crops up less than a handful of times in psychedelic-era Phoenix, making its final stand on May 20, 1967, emcee’d and eulogized by fellow veteran showgirl Rusty Russell.

June did appear in one last film, moving right into sleaze-dripping sexploitation straight from the Sixties underbelly, though The Velvet Trap unfortunately doesn’t hold a candle to the Doris Wishmans it owes its existence to. Filmed locally in Phoenix and released in 1966, it follows the repeated rapes and eventual death of short order waitress Julie (Jamie Karson), who ends up in a Las Vegas nightclub, the titular Velvet Trap, after being jilted and stranded there. Among the dancers in the charge of the club’s washed-up silent actress madam is June Harlow, whose hotcha twirls and twists survive on film only in her minutes-long strip-tease montage seen towards the finale, just before disappearing, bare-backed, behind the stage curtain. Another of her brief scenes below:

In a way, June’s observation in her 1956 Cabaret article that strippers expired promptly after living a quarter of a century became a self-fulfilling prophecy: “My early start means I haven’t wasted any of my ‘best years’. And certainly a girl has her ‘best years’ and that applies particularly to strippers. Today a girl is old in stripping by the time she is 25. If she hasn’t made it by then, she might as well give up.”

‘Giving up’ is a rough way to put it—retiring might be better—but June did one of the two, or a combination of both, just as she (if her Cabaret age holds water) was pushing the ominous 3-0, which we all know turns beauty directly to dust. One could say June found the success she was hoping for in reaching an age ‘Aunt’ Jean never saw, and of all the Harlow lookalikes to be christened and crowned her successor, June found the more divergent and empowering self-chosen path outside of Hollywood. What agency women like Mary Dees, Jean Phillips, Marjorie Woolworth, Ann Sheridan, et al. lacked in being tagged a dead woman’s replacement by a film studio was found by June Harlow in the art of burlesque, where she called the shots on crafting her own image.

Without a clue as to the name on June Harlow’s Social Security card—as it certainly wasn’t June or Jean Carpent(i)er, or even June DiMaggio, a name which rightfully belonged to a flesh-and-blood niece of the real Joe—there are no more puzzle pieces to sift through, ending her story with a question mark in bold. If this writer has learned anything in her years of sifting through stories of obscure and otherwise unsung performers, though, it’s that the question mark isn’t always a cryptic symbol of doom and certain death. In fact, it more than suits June, and leaves something of her to be desired; playful, saucy, uncertain, like she could walk back in from stage left for an encore at any time. You never know.

Sources

Special thanks to Marilyn Monroe/Joe DiMaggio expert Kelly Lacroix for confirming that Joe DiMaggio is truly not, in fact, at all related to whoever Anthony “Tony” (Russ) truly is.

1. Ad for June Harlow DiMaggio’s burlesque act, Fort Worth Star-Telegram, 24 Jun 1955, p.11.

2. Harlow, June. “I Stripped at 16.” Cabaret, vol. 2, no. 5, Sept. 1956, pp. 28–35, 45.

3. Jones, Will. “Should June Get a Head?” Star Tribune [Minneapolis], 12 Sep 1956, p 38.

4. Krug, Karl. “On the Town.” Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, 15 Sep 1959, p. 15.

5. Radcliffe, E.B. “Theater.” The Cincinnati Enquirer, 24 Aug 1957, p. 14.

6. “Dancers Nabbed In Mill City Burlesque Raid.” Grand Forks Herald, 6 Mar 1956, p. 5.

7. “What Goes on Here--Law.” The Washington Daily News, 8 Feb 1958, p. 5.

8. Ad for June Harlow’s burlesque act, The Miami News, 15 Mar 1958, p. 7.

9. “Gridiron Show ‘Roasts’ VIPs.” El Paso Herald-Post, 4 Dec 1958, p. 24.

10. “Bookie Suspects Free on Bond.” El Paso Herald-Post, 1 Jun 1959, p. 21.

11. Ad for June Harlow DiMaggio’s burlesque act, The Cleveland Press, 19 Aug 1959, p. 61.

12. “June Busts Out All Over Italy.” El Paso Herald-Post, 23 Nov 1959, p. 4.

13. McAfee, Hoyt. “Juarez ‘Strip’ Spots Irk Actors.” The Richmond News Leader, 6 Aug 1960, p. 40.

14. Hearn, Don. “Midnight Whirl’d...” The Washington Daily News, 14 Aug 1961, p. 25.

15. Various ads for June Harlow’s act in the El Paso Herald-Post and Shreveport Journal, Pensacola News Journal, Sun Herald [Biloxi], and The Arizona Republic, December 1960 to May 1967.

15. “How Do You Remember Phoenix? - Stories from Long Time Residents...” City-Data.com, 2007, www.city-data.com/forum/phoenix-area/192459-how-do-you-remember-phoenix-stories-58.html. Accessed 17 Apr. 2025.