Justine Valse Will Have Her Revenge on Los Angeles

Writing on the deluge of dreamers seeking fame or employment in Hollywood during its heyday harks back to several of Hollywood’s self-injurious moments of fascination with the pitied Extra--in particular, one scene in the original A Star Is Born (1937), where the clerk at Central Casting tries to talk a starry-eyed Esther Blodgett down from her ivory tower by bluntly leading her into the PBX room where dreams go to die.

“Every one of those little lights thought it was going to be a star,” the clerk says of the interminable flashes illuminating the switchboard, before eulogizing Esther with a claim that her chances of becoming a movie star were one in a hundred thousand.

The numbers are everywhere. As Esther enters the building, the camera lingers on her long look up at a Central Casting billboard that demands to know if she understands the figures. 5,393 women, 5,517 men, and 1,506 children make 12,416 mouths to feed, of which only a fraction, around 700, would find themselves before cameras each working day. Numbers figure largely in another tale of filmdom failure, The Life and Death of 9413: a Hollywood Extra (1928), in which a hopeful has his place in line branded on his forehead as a reminder of the cruelty he was willing to endure, losing his identity in the process. Even his mail is addressed to ‘Mr. 9413’—a number that follows him all the way to heaven, where it is finally cleared in a moment of divine transference that satirizes Hollywood’s need for a happy ending.

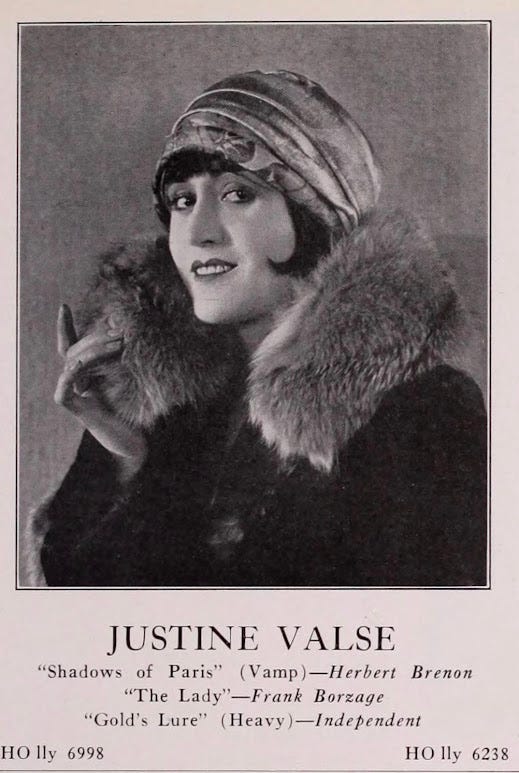

In reality, the 9,413—or 12,416—weren’t simply blessed with the luck of having their sins absolved at the end of the reel to satisfy the audience. One of them was vampiric silent actress Justine Valse, whose tempestuous years in Jazz Age Hollywood all but earned her a full sash of Girl Scout badges for the variety of trials placed in her lap—but to understand the middle, we have to start at the beginning.