I liked My Heart Belongs to Daddy (1942)—an attempted comedy—in spite of itself, because its highly watchable plot concerning a pregnant Randesque bubble dancer who accidentally traps a widowed astrophysicist badly in need of liberation from his stuffy in-laws with fatherhood after he comes to her rescue during labor trumps both its enjoyability and originality. Its professor-showgirl dynamic leans heavily on the recent triumph of Hawks’ Ball of Fire (1941), though, as you can probably tell by its obscurity as a Paramount programmer, it keeps just about none of the sparkling charm and humor present in its older cousin, and is rather like a dying lighter one keeps trying to get a spark out of; the nod to Cole Porter in its title stands near the apex of its wit, and we don’t even get to hear the song performed on film (though we came tantalizingly close to and disappointingly far from having the woman who popularized the song, Mary Martin, be our leading lady).

Canned working titles for My Heart Belongs to Daddy included the cute but underwhelming Special Delivery, and the seemingly unrelated Washington Escapade; the film was known by the latter when its casting process was discussed in trade magazines as early as December 1941, just before the finished Ball of Fire’s belated premiere. AFI doesn’t note filming on My Heart Belongs to Daddy starting until January 27, 1942, which leaves more than enough of a window for Paramount to crib a little from RKO.

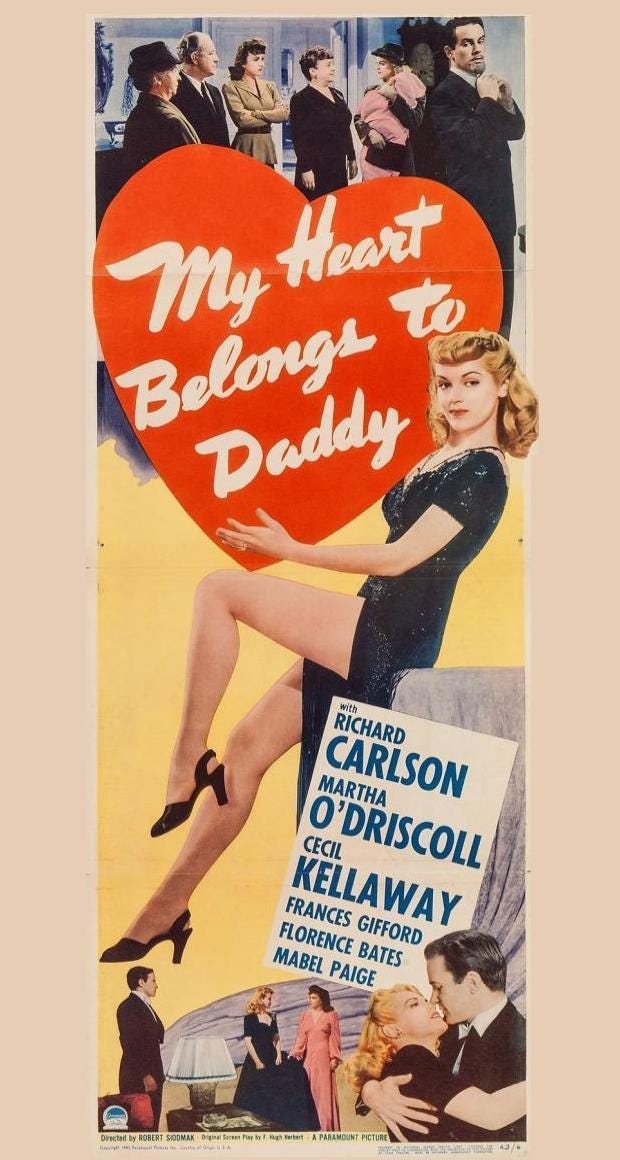

Richard Carlson as our leading man, Professor ‘Rick’, looks more Tsarist-era Eastern Orthodox than distinguished professor with his pasted-on pair of bushy eyebrows and beard, but it doesn’t distract from his character; it seems right in line with the wacky scenario that drops us along with Martha O’Driscoll’s showgirl Joyce Whitman right into the good-natured Professor’s sprawling mansion after her cab stalls in a snowdrift on the way to the hospital to have her baby—the Professor’s guest room proves a good enough substitute. Mother and child prove too weak to be moved, and the tolerant, doting attention the Professor showers on his new charges leads to second-chance romance and happily after ever.

Despite its status as a wartime post-Coder, which frequently tip-toe and proselytize around the idea of unwed pregnancy in ways my favorite pre-Codes don’t, My Heart Belongs to Daddy doesn’t make an issue of the baby’s fatherhood or its legitimacy—because Joyce has conveniently been widowed as well. Her nightclub profession and social standing more than come into question by the Professor’s stale in-laws taking up space in his home after the death of his wife, as well as Joyce’s own in-laws who turn hellbent on wrestling her for custody of her baby; what could have been handled as a riotous influx of in-laws, like My Man Godfrey (1936) or Arsenic and Old Lace (1944), instead falls victim to a curiously noirish treatment from director Robert Siodmak, whose best known films (Phantom Lady, Christmas Holiday) emphasize his misplacement in being tasked with breathing life into a burgeoning screwball.

F. Hugh Herbert, who wrote the original screenplay, can at least share in a portion of the blame for the flavorless quality of the final product, though it was beyond his control that a promising scene where Martha O’Driscoll’s Joyce strips out of her sister-in-law’s gown in front of the Professor was given as much oomph as a funeral parlor. Another less pressing issue of that of the moderate forgettability of O’Driscoll, whose entire body held the same amount of charisma Barbara Stanwyck or Mary Martin kept in their pinky fingers. O’Driscoll, who had just stepped out of Deanna Durbin flicks and kiddie college musicals into full-fledged adult roles, simply doesn’t have the personality or experience to be a convincing hardboiled showgirl, though she’s to be commended for putting her best foot forward.

Siodmak delves straight into staid dramatic scenes between Professor Rick and his mother and sisters-in-law that take up entire swathes of the film, while our enjoyable but underequipped leading lady is relegated to equally long periods of offscreen postpartum bedrest. At times the dark pleading eyes of Florence Bates’ pearl-clutching mother lead us to believe we’ve gone off the deep end into psychological horror, just for the Professor’s slapstick beard (which he’s luckily made to shave off) to set the tone back where it belongs. Siodmak’s moodiness doesn’t even benefit from being compelling, which poses the question of just how well Herbert’s screenplay could have cleaned up if visualized by a director possessing a heftier ounce of upbeat wit. This undeserving B obviously didn’t deserve the lavish production typical of a Wilder, Lubitsch, or Capra, but Siodmak is so wildly out of his element in screwball that one can’t help but wonder how much better it could have fared. Despite its astounding lack of passion and spontaneity (I’m not sure the leads touch each other more than once), the film remains unfailingly sweet and tender, though the dismal overtone will have the true yearner seeking out another fix like a child with unfinished dinner returning to the kitchen for desert.

Sources

1. “Notes from Hollywood.” Motion Picture Daily, 31 Dec 1941, p. 5.